Let’s Examine Examiners

To many, FTX’s bankruptcy seemed like a paradigmatic case for appointment of an examiner. The issues were complicated, the history opaque, the industry and legal questions novel, and even given the appointment of a well-respected and credible new CEO there were non-frivolous concerns about the independence, timing and disclosure of investigations. Given the amount of the projected examiner’s bill, the bankruptcy court ruled against a “costly investigation that would slow the progress of these cases.” The Third Circuit recently reversed that decision and came down strongly in favor of appointment of an examiner and more generally in favor of the right to demand appointment of examiners.

Is there now more leverage to demand an examiner in a less complicated case, or perhaps to forego that demand in exchange for some consideration? Is this yet another decision that will move cases away from the Third Circuit? What do you think of the Third Circuit decision? Where would you draw the line on demands for appointment of an examiner?

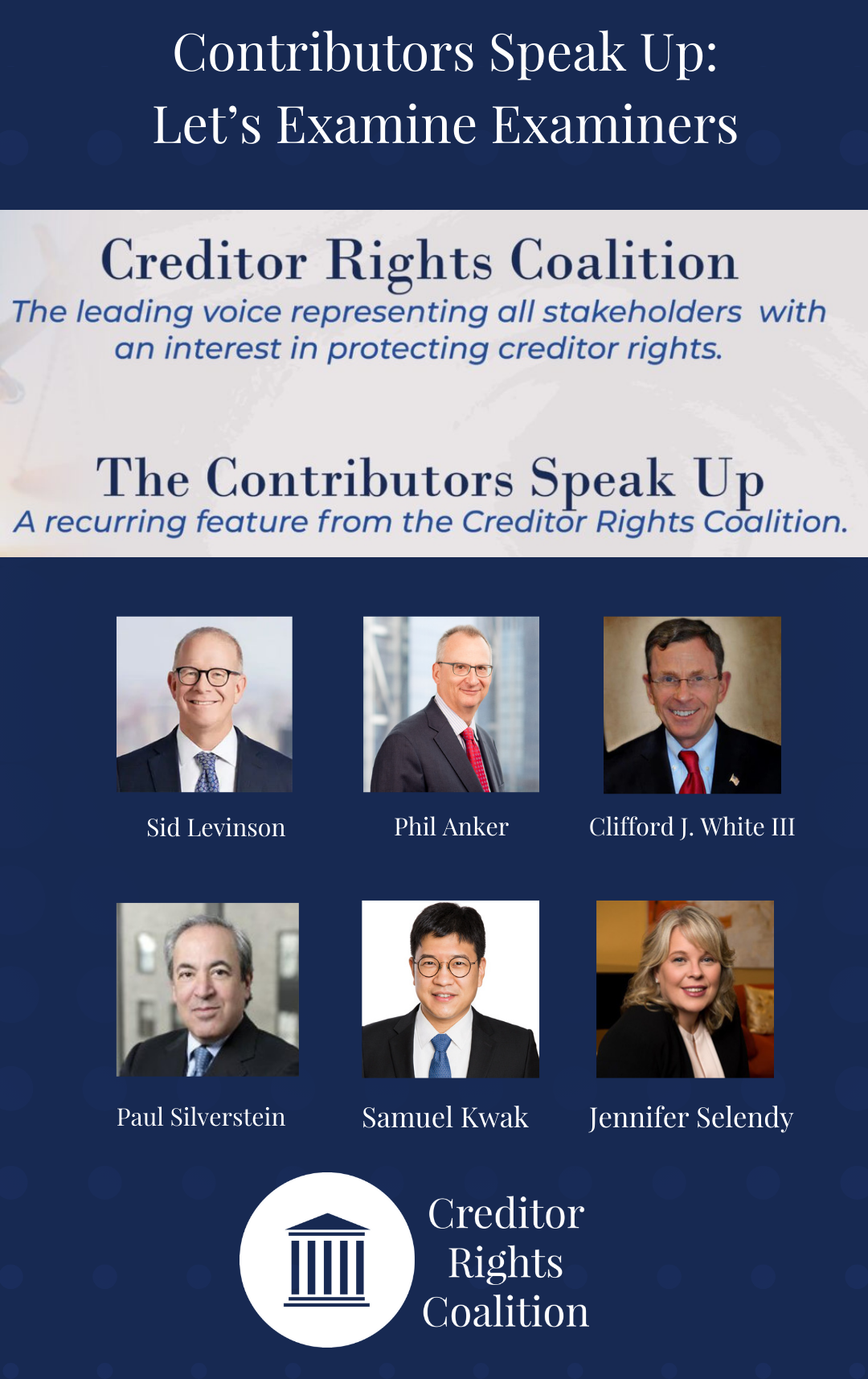

In advance of the March 20 hearing in the FTX case, we asked our expert Contributors to weigh in.

Phil Anker

Wilmer Hale

From my perspective, there are two issues: what the law is, and what it should be? Put differently, what does the Bankruptcy Code, in its current form, say regarding the appointment of an examiner, and should it be amended to say something else?

The Third Circuit decided only the first of those two issues. As courts regularly do, it focused on the wording of the statute. The Code provides that, in a Chapter 11 case in which a trustee has not been appointed, the bankruptcy court “shall” appoint an examiner to “conduct such an investigation of the debtor as is appropriate,” so long as the U.S. Trustee or a party in interest so requests and the debtor has more than $5 million in fixed, liquidated, unsecured debts. Reading the word “shall” to be mandatory, the Third Circuit held that as long as the conditions are met (the debtor-in-possession has more than $5 million in fixed, liquidated, unsecured debt and the U.S. Trustee or a party in interest moves for such relief), the court must appoint an examiner, though it added that the court has considerable discretion to determine the scope of an examination that is “appropriate.” That holding strikes me as right as a matter of pure statutory construction — i.e., in deciding what the law is.

But that leaves the more interesting question: should that be the law? My answer is no. Especially in a case like FTX where no creditor or other party in interest with an economic stake in the outcome of the case requests the appointment of an examiner, and where the judge presiding over the case sees no need for an examiner, I am hard pressed to see why one should be required. Why should the estate (and, thus, the economic stakeholders) have to pay for the examiner’s counsel and other professionals to conduct an investigation, and potentially delay the development of a Chapter 11 plan that can return some value to the creditors and other stakeholders, particularly where a creditors committee has been appointed and has retained experienced professionals who can conduct their own investigation into the debtor and potential estate causes of action? After all, the principal goal of Chapter 11 is not to foster an inquiry into the circumstances that led to the debtor’s downfall, for the supposed benefit of the public at large; Congressional, regulatory and other investigations can perform that function, and there have, in fact, been many such investigations regarding the crypto sector in general and regarding FTX in particular. It is, instead, the main objective of Chapter 11 to maximize the recovery for creditors and the saving of jobs through the reorganization, if possible, of the debtor’s business.

So, while it is hard to imagine that the current Congress will accomplish much of anything, I would favor an amendment to the Code so that the appointment of an examiner is not mandatory in cases in which no creditor or other economic stakeholder requests or supports such an appointment. Alternatively, if the only party in interest that wants an examiner is the U.S. Trustee, the Code could be amended to require that the federal government pay the freight. If it is truly in the “public interest” for an examiner to be appointed, then the public should pay for it. Maybe that approach, rather than one that allows one party (the government) to require another (the debtor’s bankruptcy estate) to pay for an examination, will cause there to be a careful weighing of the costs and benefits of appointing an examiner.

Sid Levinson

Debevoise & Plimpton

When Congress enacted Chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code in 1978, it authorized the appointment of an examiner in large cases (i.e., exceeding $5 million in unsecured debts) as a means to “adequately represent the needs of public security holders in most cases.” H.R. Rep. 95-595, 1978 U.S.C.C.A.N. 5963, at 6534. But importantly, Congress also enacted section 1109 (authorizing the SEC and any party in interest to appear and be heard on any issue in a bankruptcy case) as a means to jettison the approach under former Chapter X, in which public interest was often determined “only in terms of the interest of public security holders,” in order to “enable the court to balance the needs of public security holders against equally important public needs relating to the economy, such as employment and production and other factors such as the public health and safety of the people or protection of the national interest.” Id. at 6534–35.

This legislative history serves as a useful backdrop to the ongoing debate over examiners and the requirement to appoint them under section 1104(c). Over the nearly 50 years since enactment of the Bankruptcy Code, legitimate questions have been raised about the efficacy of examiners and the value they provide in Chapter 11 proceedings. To be sure, there are cases — Caesars comes immediately to mind — in which an examiner has performed an invaluable role in shining a bright light on dubious transactions and persuading otherwise recalcitrant parties to resolve their disputes. But in other cases, examiners have been criticized for taking too long and spending too much money to produce reports that fail to provide definitive guidance on dubious transactions. And, of course, the right to seek mandatory appointment of examiners has been abused by creditors and other parties to cause delay of bankruptcy proceedings, often on the precipice of plan confirmation.

As Congress observed in 1978, when it jettisoned many “archaic rules” of prior bankruptcy law that predated enactment of the Trust Indenture Act and the development of securities laws, “the benefits of these provisions have long been outlived but the detriment of the provisions served to frustrate and delay effective reorganization in those chapters of the Bankruptcy Act in which such provisions applied.” Id. at 6535. As both bankruptcy law and the restructuring practice have evolved over the past 50 years, the Bankruptcy Code’s mandatory appointment of examiners in large cases seems increasingly “archaic,” particularly to bankruptcy judges on the front lines who have stretched to interpret section 1104(c) in a manner that provides for flexibility in appointment of examiners. Ultimately, it has become evident, most recently in the FTX bankruptcy, that the most effective tool available to bankruptcy judges is their discretionary authority to dictate the scope, duration and cost of any examination, as a means to appropriately balance the interests of “public security holders” with those of “public needs,” including the ability to facilitate a quicker and less expensive reorganization.

Paul Silverstein

Hunton Andrews Kurth

Mandatory Appointment of Examiner: 3rd Circuit in FTX makes clear that “Shall” means “Shall”

That a bankruptcy court could find, in the context of a mandatory examiner motion under section 1104(c)(2) of the Bankruptcy Code, that the words “shall order” do not mandate an examiner appointment illuminates that bankruptcy courts are fundamentally in the business of facilitating the prompt emergence from Chapter 11 of large complex debtors. The Bankruptcy Code is, and was intended as, a debtor statute; but there must be limits and respect for clear statutory mandates. The 3rd Circuit’s recent FTX decision, a very straightforward and simple decision, makes clear that the word “shall” means “must” and a motion for appointment of a mandatory examiner must be granted when the requisite dollar amount of unsecured debt exists.

Notwithstanding existing Delaware bankruptcy court precedent for the proposition that “shall” does not mean “shall”, it was nonetheless surprising that the Bankruptcy Court declined to appoint a mandatory examiner in FTX on the United States Trustee’s motion. FTX is a significant and novel case allegedly involving massive fraud and management improprieties. Indeed, as the 3rd Circuit remarked, it also appeared that one of FTX’s pre-petition counsel, who was retained as debtor’s counsel, allegedly was involved in FTX’s pre-petition businesses and allegedly selected FTX’s post-bankruptcy CEO. In overruling the FTX Bankruptcy Court, the Third Circuit stated: “The meaning of the word ‘shall’ is not ambiguous. It is a ‘word of command’… that ‘normally creates an obligation impervious to judicial discretion.’… We have held that ‘shall’ in a statute is interpreted as ‘must’ which means ‘shall’ signals when a court must follow a statute’s directive regardless of whether it agrees with the result ….” (No. 23-2297, 1/19/24 at pp. 9–10). Further, it was also surprising that the FTX Bankruptcy Court, like many other courts which found “shall” not to mean “shall”, ignored the legislative compromise that resulted in a mandatory examiner provision under the Bankruptcy Code. Under Chapter X of the former Bankruptcy Act of 1898, as amended, the appointment of a trustee was mandatory. The compromise between competing House and Senate versions of what became the Bankruptcy Code was that (a) the appointment of a Chapter 11 trustee would be discretionary requiring a showing of either “cause” or the best interests of creditors, stockholders, or the debtor’s estate and (b) if a trustee was not appointed, an examiner would be mandatory on motion of a party in interest if unsecured claims exceed $5 million excluding trade and insider debt.

Why did “shall” not mean “must” in the view of those courts? There are basically two seemingly obvious reasons. First, particularly when a mandatory examiner motion is made by the United States Trustee, as opposed to a party with a financial interest, and the court views the debtor to have competent and sophisticated management and experienced professionals, many courts view an examiner as an unnecessary expense and distraction. In a very early case under the Bankruptcy Code, one Court, after acknowledging that unsecured debt exceeded the requisite $5 million, found that a mandatory examiner appointment would delay and impose substantial unnecessary costs on the estate and stated: “to slavishly and blindly follow the so-called mandatory dictates of [the mandatory examiner provision] is needless, costly and nonproductive and would impose a grave injustice on all parties.” Second, when a mandatory examiner motion is made by a creditor, stockholder or other party in interest who is not pleased with the direction of the case, such motion is often viewed as strategic or tactical, intended to slow down the case and harmful to the debtor’s efforts to emerge from Chapter 11, particularly when the motion is not filed immediately after the filing.

It is no surprise that debtors (and official committees) in large, complex cases rarely, if ever, move for the appointment of a mandatory (or discretionary) examiner. They likewise generally oppose motions for the appointment of an examiner on the grounds that the debtor and/or official committee can conduct any appropriate investigation. Debtors (and official committees) have investigative duties under the Code and are handsomely paid for such work. Why would they want to “empower” constituents who are not then on board with the direction of the reorganization with an independent and disinterested examiner? Why would a debtor or official committee risk having a disinterested examiner, with no financial or other interest in the outcome of the case, conduct an investigation of fraud, wrongdoing, financial improprieties or similar matters when the debtor and its agents, advisors, and any official committee and its advisors, have spent, or are budgeted to spend, millions on similar investigations? Ad hoc groups of creditors or stockholders with agendas not aligned with the debtors, creditors committees or RSA parties generally do not have the resources of those parties with retained professionals. Ad hoc groups often use examiner motions as a leverage device that they would then try to “settle” or withdraw in exchange for a remedy including, for example, being granted standing to pursue estate claims (with funding in connection therewith). An obvious risk an ad hoc group faces with an examiner motion is that if they can’t “settle,” they may not like the results of an examiner’s investigation.

With the very clear pronouncement of the 3rd Circuit in FTX, how will motions for mandatory examiners be addressed in future cases? Section 1104(c) provides that the court shall appoint an examiner to “conduct such an investigation of the debtor as is appropriate, including an investigation of any allegations of fraud, dishonesty, incompetence, misconduct, mismanagement, or irregularity in the management of the affairs of the debtor of or by current or former management ….” (Emphasis added.) One would think that in granting an early motion for a mandatory examiner by the United States Trustee the scope of the investigation would be broad and not limited. On the other hand, when faced with a “strategic” motion for a mandatory examiner by a party with an economic interest in the case, bankruptcy courts will likely show flexibility in limiting or tightly tailoring the scope of the examiner’s investigation, budget and timeline given the facts of the case, including how close it is to confirmation. When the appointment of an examiner is mandatory, the obvious issue will be the appropriate scope of the examiner’s investigation, budget and timeline. The likelihood of appellate review of a bankruptcy court order setting a narrow examiner scope would be very limited. Because the scope of an examiner’s investigation is a factual matter, on appeal the appellate court must accept or give deference to the bankruptcy court’s factual findings unless they are clearly erroneous and give due regard to the bankruptcy court’s opportunity to judge the credibility of witnesses and evidence.

Clifford J. White III

In this space last year, I penned a commentary asking: “Where have all the examiners gone?” Well, we just found an important one that may portend more examiners in the future. That is a good thing. In January, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit reversed the bankruptcy court and ordered the appointment of an examiner in the FTX Trading LTD, et al., case. The court’s opinion was straightforward and to the point — when Congress said “shall” in section 1104, it meant “shall.”

In the words of the Third Circuit, “[s]ometimes highly complex cases give rise to straightforward issues on appeal.” In this case, Congress divested bankruptcy judges of discretion and mandated that they grant motions to order the United States Trustee (UST) to appoint an examiner in cases meeting certain debt level requirements. Despite all the hand-wringing by the debtor and unsecured creditors committee, the circuit court found the result was clear in “both the statute’s plain text and Congress’s expressed intent in enacting this portion of the Bankruptcy Code.”

The opinion is sure to be influential in other circuits and may put an end to the statutory construction gymnastics of those who want to deprive parties and the public of an independent examination of major companies that go bust with hints of fraud or other shenanigans.

The Battle May Not Be Over

Once a court orders the appointment of an examiner, more fun begins. In FTX, having unsuccessfully tried to write the mandatory examiner provision out of the Code, lawyers for the debtor and unsecured creditors committee urged the court to ignore the statutory provision that gives the United States Trustee exclusive power to appoint examiners, subject to court approval (essentially for eligibility, mainly disinterestedness). Instead, without any authority or precedent, they tried to repeal the 1978 Code which got judges out of the appointment business by saying the judge should appoint from candidates put forth by selected parties and the UST. Fortunately, the judge gave short shrift to that frivolous argument which hopefully will not be used in future cases by parties who wish to delay and obstruct an independent examination.

The next issue to be resolved in FTX, as in all cases, is scope. That is a perfectly legitimate issue for the court to consider. In FTX, the Circuit made clear that, even though a substantial period of time elapsed between the UST’s motion and its resolution, there were plenty of issues worth investigating. For example, the Circuit Court said that the manipulation of the company’s value and broader issues about cryptocurrency merit independent review for the benefit of stakeholders who would vote on a chapter 11 plan, as well as the general public. The Court also recognized the importance of a disinterested examiner, noting that “is particularly salient here, where issues of potential conflicts of interest arising from debtor’s counsel serving as pre-petition advisors to FTX have been raised repeatedly.”

The UST traditionally argues for a broad scope to fulfil the needs of both the stakeholder and public interests. The debtor and committee usually resist giving up any investigatory turf. Unlike private litigants, an examiner, who is a “court fiduciary” in the words of case law, should preempt the field and shut down expensive, free-for-all discovery in favor of a more orderly process. Also, the examiner is in the best position to navigate multiple investigations by the company and law enforcement authorities. Finally, and as emphasized by the Circuit, the examiner files a public report that is vital in high-profile cases of great public interest and economic impact.

Ironically, in FTX, the debtor and committee, which have incurred hundreds of millions of dollars in professional fees that are growing every six minutes, said the estate simply should not have to pay additional costs. That argument, when made in a case with such astronomical fees and so much public interest at stake, is hard to take seriously. But that argument is commonly made by controlling parties to limit the scope of the investigation in mega-cases.

The bankruptcy judge had some sympathy for that argument but conceded that the Circuit found areas in need of review. The court said it plans to limit the initial investigation to 45 days and to identify any areas not satisfactorily investigated by others prior to the examiner appointment. That approach is not offensive, as long as the court remains open to expansion of the scope based on the recommendations of the examiner after an initial review.

Game Changer

The FTX examiner decision may be a game-changer. Entrenched debtor management and the most powerful creditors, and their lawyers, may find themselves with a slightly loosened grip on mega-chapter 11 cases. The threat of an independent examination may chasten parties to respect broader interests in the case and to reduce runaway professional fees.

As cited by the Third Circuit, the U.S. Trustee Program (USTP) filed only about 10 examiner motions in the previous year. Although the Program will still be selective in filing motions, I would not be surprised if the Program files about three times as many examiner motions in the future. There are at least that many mega-cases of substantial public interest that are burdened by questions of fraud, egregious mismanagement, or other issues meriting independent review. This will make chapter 11 case administration more transparent and efficient. Although many parties will argue for crabbed limitations on scope of review, the system will increasingly be amenable to robust independent investigations.

If monied parties in a case use their new leverage to file examiner motions solely for strategic advantage, the courts will and should limit the scope. Nonetheless, the scope should never be so limiting as to deny a bona fide investigation that is allowed by Congress in section 1104. If time shows that courts and estates are besieged by examiner requests that ill-serve the public and estate interests, then Congress should step in.

If there is clear overuse of the mandatory examiner provision for litigation advantage purposes, then Congress should consider requiring private parties to satisfy the section 1104(c)(1) prong of the current test and prove that the appointment would be in the interests of the estate. The mandatory appointment under paragraph (2) could be reserved for the UST. This approach would be consistent with the limitation placed on creditors in section 707(b)(6). Under that provision, only the judge or UST can bring a motion to dismiss a below median-income consumer debtor’s case based on the “abuse” standard.

The Future of Examiners

The FTX decision should cause a needed and significant uptick in examiner motions and UST appointments. That should be welcome news for those who are concerned about the transparency and costs of modern mega-chapter 11 case administration. Bankruptcy courts have authority to rein in creditor misuse of mandatory examiners. The Third Circuit decision will be influential and likely followed by other courts throughout the country.

Samuel Kwak & Jennifer Selendy

Selendy Gay

On January 19, 2024, the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit reversed the bankruptcy court’s denial of the U.S. Trustee’s motion in the FTX’s Chapter 11 case (In re: FTX Trading Ltd.), concluding that the appointment of an examiner was mandatory under the Bankruptcy Code Section 1104(c)(2) upon satisfaction of the requirements specified thereunder. This decision by the Third Circuit is a substantial one that is likely to have some lingering effect in the landscape of large-scale corporate restructuring cases.

Most notably, the status of the District of Delaware as one of the most popular bankruptcy venues may be at risk. Given the Third Circuit’s binding ruling, the bankruptcy courts in the District of Delaware have to appoint an examiner upon satisfaction of the statutory requirements under Section 1104(c)(2). Some popular bankruptcy venues—such as the Southern District of New York and the Southern District of Texas—have reached the same conclusion as the Third Circuit in some decisions. See, e.g., In re Loral Space & Comm., Ltd., 2004 WL 2979785, at *4 (S.D.N.Y. Dec. 23, 2004); In re Erickson Ret. Cmty., LLC, 425 B.R. 309, 312 (Bankr. S.D. Tex. Mar. 5, 2010).

However, other decisions by the same court sometimes suggested otherwise. For example, Chief Judge Martin Glenn of the Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of New York has concluded that “the facts and circumstances of the case may permit a bankruptcy court to deny the request for appointment of an examiner even in cases with more than $5 million in fixed debt,” In re Residential Cap., LLC, 474 B.R. 112, 120-21 (Bankr. S.D.N.Y. 2012); see also In re Dewey & LeBoeuf LLP, 478 B.R. 627, 639 (Bankr. S.D.N.Y. 2012). This ruling is in direct conflict with the Third Circuit’s decision in the FTX case. These precedents, together with the absence of controlling Second Circuit authority on the appointment of an examiner, could make the Southern District of New York an attractive bankruptcy venue for any debtor that is concerned about the examinership being abused by its stakeholders as a means to gain tactical advantage.

The Debtors, however, may not need to stay away from the Third Circuit solely because of the concern about an examinership. As noted by the Third Circuit, a bankruptcy judge still retains a significant amount of discretion regarding the investigation by an examiner, even if the appointment of one may be mandatory. In re: FTX Trading Ltd., 91 F.4th 148, 156 (3d Cir. 2024) (“the court retains broad discretion to direct the examiner’s investigation, including its scope, degree, duration, and cost”).

Against this legal landscape, a Company contemplating a Chapter 11 filing may consider conducting an independent investigation before the filing. There are several foreseeable benefits:

First, by uncovering facts that could lead to disputes in its Chapter 11 case, the Company can try to address potential issues in advance of the filing or at least have a better sense of how its Chapter 11 case will play out. Advanced planning can significantly enhance the possibility of a successful restructuring, especially given the expensive costs a Company bears each day it spends in a Chapter 11 proceeding.

Second, conducting an investigation pre-filing could result in significant saving of estate assets. In bankruptcy, an examiner’s scope of investigation is within the discretion of the bankruptcy judge. However, an examinership can be extremely expensive—in fact, based on FTX’s submission to the bankruptcy judge, the cost of an examinership could be as high as $100 million. The expedited timeline of investigation called for by the bankruptcy process could further drive up the final bill.

In contrast, conducting an investigation pre-filing can allow a Company to explore various options to economize the investigation and utilize the information generated in the course of the investigation to further polish its direction. Then, after filing, the Company can leverage the record of its pre-filing investigation to persuade a bankruptcy judge that the scope of investigation by an examiner should be limited. The cost savings and efficiency that can be achieved by proceeding this way can help a Company emerge from bankruptcy in a much stronger position.

The views of our Contributors should not be attributed to their respective firms or the Creditor Rights Coalition. In addition, the Coalition may take positions as part of its Advocacy efforts that do not necessarily reflect the view of Contributors and should not be attributed to any Contributor.