Weekly News – August 25

The Academics Speak Up

Professor Ralph Brubaker

University of Illinois

I, for one, applaud the Supreme Court’s decision to finally address the permissibility of so-called nonconsensual nondebtor (or third-party) “releases†and “channeling†injunctions that discharge the obligations of nondebtor entities who have not themselves filed bankruptcy. And I am grateful for the tenacity of the U.S. Trustee and DOJ in calling out the utter impropriety of nondebtor-discharge practice, which has tainted the bankruptcy system and incited public outrage. These nondebtor discharge provisions are illegitimate and unconstitutional, and the Supreme Court should emphatically repudiate them.

Courts’ approval of nondebtor discharge provisions contravenes the separation-of-powers limitation embedded in the Constitution’s Bankruptcy Clause, which gives Congress the exclusive power to authorize discharge of indebtedness and to prescribe the circumstances under which such a discharge is appropriate. The nonconsensual nondebtor “release†(i.e., discharge) jurisprudence of those courts permitting the practice is also an unconstitutional exercise of substantive federal common lawmaking, in violation of the federalism and separation-of-powers constraints established by Erie R.R. Co. v. Tompkins, 304 U.S. 64 (1938). Moreover, the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence for interpreting the Bankruptcy Code directly incorporates those constitutional limitations, which cogently elucidate why nothing in the Bankruptcy Code can plausibly be read to authorize nonconsensual nondebtor releases.

The desire to facilitate settlement of complex mass torts cannot justify nondebtor-discharge practice. With the nonconsensual nondebtor-release device, the federal courts have manufactured out of whole cloth the unique, extraordinary (and unconstitutional) power to impose a mandatory no-opt-outs “settlement†of a nondebtor’s mass tort liability on unconsenting tort victims through the bankruptcy proceedings of a co-defendant. The process by which nonconsensual nondebtor releases are negotiated, proposed, and approved violates nonconsenting claimants’ constitutional due process rights, both by denying them an adequate, unconflicted litigation representative, and by denying them any opportunity to exclude themselves from what is a mandatory no-opt-outs “settlement†process that is involuntarily imposed upon them. Moreover, nonconsensual nondebtor releases unconstitutionally abrogate nonconsenting claimants’ Seventh Amendment jury trial rights by extinguishing traditional private-rights damages actions against nondebtors for which claimants have constitutional rights to both jury trial and final judgment from an Article III judge. What’s more, the bankruptcy “necessity†that supposedly justifies this astounding and unique settlement power—to mandate nonconsensual no-opt-outs “settlements†that are otherwise impermissible and unconstitutional—is nothing more than empty, false rhetoric that is a product of (at best) naive credulity or (at worst) specious sophistry.

Nonconsensual nondebtor releases are not “necessary†for the bankruptcy process to facilitate efficient aggregate settlements of the mass tort liability of both bankruptcy debtors and nondebtor co-defendants. The bankruptcy jurisdiction, removal, and venue provisions of the Judicial Code already contain the essential architecture for mandatory, universal consolidation of tort victims’ claims against both bankruptcy debtors and nondebtor co-defendants. Bankruptcy can be an extremely powerful aggregation process that facilitates efficient (and fair) settlements of the mass tort liability of nondebtors, even (and especially) without nonconsensual nondebtor releases. Nondebtor releases are an illicit and unconstitutional means of forcing mandatory settlement of unconsenting tort victims’ claims against nondebtors, and the Supreme Court should resolve the longstanding circuit split over the permissibility of nonconsensual nondebtor releases by categorically renouncing them.

Copyright © 2023 Ralph Brubaker. All rights reserved.

Professor Anthony J. Casey

University of Chicago

As the bankruptcy of Purdue Pharma heads to the United States Supreme Court, the bankruptcy world is once again in a frenzied debate about “third-party†or “nondebtor†releases. This debate often devolves, unfortunately, into one of rhetoric producing, as they say more heat than light.

It can be difficult to address all the nuances in short form. I have laid out a long-form academic argument in favor of nondebtor releases elsewhere. And I have addressed some of the policy considerations here and here. But it may be useful to use this space to counter two of the weaker arguments against nondebtor releases. The first is that releases let wrongdoers escape consequences. The second is that the Bankruptcy Code prohibits nondebtor releases. Neither of these arguments stands up to scrutiny.

- Releases do not let wrongdoers escape consequences.

Nondebtor releases of the type found in Purdue are not“rare and controversial†provisions that let wrongdoers get off nearly scot-free. In the first place, it should be obvious to anyone with even a basic understanding of bankruptcy law that these releases have no effect on criminal prosecutions. No bankruptcy proceedings can have such an effect. Any decision to go (or not go) after the Sacklers criminally was—or will be—made by government actors independent of any authority of the bankruptcy court.

More importantly, nondebtor releases are granted in exchange for substantial contributions from the released parties. They are only approved when the releases are deemed essential to reorganization and supported by overwhelming majorities of claimants, and when the contributions make those claimants better off.1 In this form, they have become fundamental tools for resolving exceptionally complex mass tort cases that involve thousands of claimants.

Indeed, for decades nondebtor releases have played a critical role in some of the most important bankruptcy settlements in the United States. For example, when Dow Corning faced thousands of lawsuits related to defective breast implants, nondebtor releases facilitated a negotiated resolution that had failed several times without them. In exchange for a settlement of claims against them, solvent shareholders agreed to contribute to a settlement fund. The overwhelming majority of claimants (94%) supported the deal. But what about that last 6%? The court had a choice: use releases to force the 6% to go along or let things drag on for years or decades in uncertain litigation. The court chose the former in order to get desperately needed money to the victims.

This was the right choice. As one prominent scholar noted in describing the releases in Dow Corning, “The whole point of bankruptcy is to find the fairest deal possible for everyone involved,†and a resolution supported by an overwhelming majority of victims is “a good thing that deserves praise.â€

Similarly, in Purdue over 95% of the 120,000 voting claimants approved the releases in question. Yet, the bankruptcy judge in that case was unfairly vilified for even considering these releases as part of a multibillion-dollar global settlement. In particular, he was subjected to the absurd suggestions by academics (some of whom previously praised the Dow settlement) and politicians that he was approving the settlement in a competition to attract future cases to his courtroom even thoughthe majority of federal courts (and many courts abroad) allow nondebtor releases in the same circumstances.2

To be clear, Dow and Purdue are not outliers. Nondebtor releases have facilitated settlements in dozens of mass tort bankruptcies, including those of A.H. Robins and Johns-Manville. Indeed, the more general idea of coordination in favor of the collective good is a core feature of the bankruptcy process.

- The text of the Bankruptcy Code does not prohibit nondebtor releases.

A new sort of faux textualism has arisen in the recent bankruptcy debates. Critics who normally shy away from the label of textualist have now adopted refrains about nondebtor releases violating the sacred text of the Bankruptcy Code.

I have never considered myself much of a strict textualist, but the textual argument for nondebtor releases is far stronger than any argument against. As the Second Circuit noted, the Bankruptcy Code expressly provides in § 1123(b)(6) that a plan may “include any other appropriate provision not inconsistent with the applicable provisions of this title.†And, indeed, no other provisions of the Code prohibit nondebtor releases.

Courts and litigants often talk about this in terms of equitable judicial authority. But this framing misses the point. Section 1123 is a clear statutory grant of authority to a debtor3 in writing a plan. The Code then provides in § 1129 that bankruptcy courts shall confirm plans that complies with § 1123 (and all other provisions of the Code). It is not textualism to prohibit a court from approving what the text says it can and shall approve. And only a faux textualist—worried more about constraining courts and debtors than enforcing text—would argue that we must limit a textual grant of authority simply because it is stated in broad terms. This is a dangerous path of interpretation that would draw into question decades of judicial interpretation of other broad phrases in the Code like “fair and equitable†and “for cause.â€

Some of these textualists look for support in the limiting principles the Supreme Court announced in Czyzewski v. Jevic Holding Corp., 580 U.S. 451 (2017). These arguments get things backward. The message in Jevic was that debtors cannot evade the requirements of Chapter 11. The main feature of Chapter 11 is that it includes a specific set of protections for the plan confirmation process. These protections include the best interest of creditors test, the absolute priority rule, and a good faith requirement. That is exactly why the broad language of § 1123 is found in Chapter 11 of the Code and stated in terms of what a plan can do. Because these releases are not otherwise available, § 1123 ensures that the releases will require approval by vote and full judicial review.

The new textualists make other arguments based on negative inferences from § 524(g), which allows for nondebtor releases in asbestos cases. As others have pointed out, these arguments are foreclosed and belied by the text of the legislation itself, the legislative history, and the Supreme Court’s bankruptcy jurisprudence. They are also inconsistent with common sense. One would have to believe that Congress observed the success of settlement innovations in one category of mass torts settlements, decided to bless that innovation with §524(g), and then simultaneously decided to prohibit all similar innovations for mass tort cases.

One can doubt how serious these critics really are about statutory text. After all, many of them support the dismissal of the bankruptcy of LTL Management (the Johnson & Johnson Talc case). The Third Circuit dismissed that case on the grounds that the debtor was not in imminent financial distress. In short, J&J and LTL were acting in bad faith because they had made too much money available to cover potential liabilities.

That is a perverse outcome. Especially when one considers that, no matter how many times you read the Bankruptcy Code, you cannot find the provision that requires imminent financial distress. One might expect the new textualists to point this out and object to the Third Circuit’s ruling. They have not, likely because their objections are not really about text. For what it’s worth, my own view is that the Third Circuit ruling in LTL is wrong not because it lacks textual support (even though it does) but because it is a judge-made rule that simply makes no sense.

In the end, there is always a balance. Text matters and laws should make sense. Things can get difficult if those principles conflict. Fortunately, here and in other large mass tort cases like LTL, text and common sense both point to the same outcomes. Bankruptcy law should and does provide the necessary tools for global settlement of mass torts when those settlements are fair and broadly supported. It would be unfortunate if the Court holds otherwise in this case.

1 These protective requirements have been applied by most courts. But the Second Circuit in Purdue announced a particularly exacting fact-intensive seven-factor test for the approval of nondebtor releases. Moreover, the court announced that a bankruptcy court’s application of that test is always subject to full de novo review by the district court. This ruling further narrows the universe cases in which nondebtor releases will be granted in the future.

2 It is not just courts that think these releases are appropriate. In 2014, an American Bankruptcy Institute reform commission made up of some of the country’s most respected bankruptcy lawyers, judges, and academics concluded that “a blanket prohibition on third-party releases was inadvisable†and that a debtor “should be permitted to seek approval of third-party releases.â€

3 Or anyone else entitled to propose a plan.

Professor Samir Parikh

Lewis & Clark University

On May 30, 2023, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed the bankruptcy court order approving a modified version of Purdue Pharma’s plan of reorganization and, in doing so, recognized the validity of nonconsensual third-party releases in limited circumstances. But in his concurring opinion, Circuit Judge Richard Wesley noted the long-standing circuit split on this issue and practically begged the Supreme Court to take up the case. On August 10, the Court obliged.

Mass tort bankruptcies highlight the schism between features that are necessary to effectuate a meaningful and timely resolution and those that are constitutionally compliant. Claimants in the Purdue case voted overwhelmingly to approve the plan of reorganization.1Â In the aggregate, the vote was over 95% in favor of plan confirmation. We know from the victim statements submitted in the case that these individuals understood the consequences of the third-party releases, but they also understood that there was little chance of a meaningful recovery without a compromise with the Sackler family.

From 2008 to 2016, Purdue paid approximately $10.4 billion in dividends to Sackler family members or Sackler-controlled entities. There is an argument that these were fraudulent transfers. Couldn’t the court have just clawed back these funds? Unlikely. A significant portion of the transfers occurred outside the applicable statute of limitations, and $4.6 billion of the funds went to pay Purdue’s federal and state taxes. The remaining balance (approximately $1.5-2 billion) is predominantly in restricted spendthrift trusts overseas. How much would have to be spent to retrieve those funds? How many years would it take? The claimants understood all of this and voted accordingly. The third-party releases were an essential part of convincing the Sacklers to contribute over $5.5 billion and fulfilling what I believe is the objective of mass tort bankruptcies: securing meritorious claimants the largest recovery possible on the shortest timeline.

The Second Circuit carved out a nice compromise in Purdue. Indeed, the scope of the releases were extremely limited and the opinion – if allowed to stand – would force courts in that circuit to run the gauntlet of a seven-factor test premised on detailed factual and legal findings.

But the pragmatism driving this resolution may be insufficient to save the practice. Many academics do not believe that bankruptcy courts have the constitutional authority to grant nonconsensual third-party releases, which raise thorny Due Process issues.2 And if the Supreme Court leans into its current textualist tendencies, nonconsensual third-party releases may no longer be available in cases like Purdue. In fact, there is a possibility that the Court could also strike down the grant of power that exists in Section 524(g) for asbestos exposure cases. If that scenario were to unfold, resolving mass tort cases would become infinitely more difficult, a terrible outcome for the victim collectives in these cases. Resolution outside of bankruptcy – either through multi-district litigation or case-by-case adjudication – can be extremely protracted and inequitable.3

What happens if the Supreme Court rules that bankruptcy courts do not have the constitutional authority to grant nonconsensual third-party releases outside of Section 524(g)? Nonconsensual third-party releases would still be available for cases involving asbestos exposure. But the truth is that modern mass tort cases rarely involve asbestos exposure.4 And what if the Supreme Court goes further and holds that bankruptcy courts lack the authority to approve nonconsensual third-party releases under any circumstances? Well, a nondebtor party making a significant financial contribution to a victims’ settlement trust in a mass torts case may be able to secure a consensual third-party release from a significant majority of current claimants.5 Those refusing to agree may be allowed to pursue their claims in other venues. The primary complicating factor in this type of scenario involves a mass tort case where future victims make up a significant portion of the claimant pool. Without the possibility of a nonconsensual third-party release in such a case, bankruptcy may no longer offer the optimal venue for resolution.

To read more about mass tort bankruptcies and the complexities they present see Mass Exploitation, The New Mass Torts Bargain, Due Process Alignment in Mass Restructurings, and Scarlet-Lettered Bankruptcy: A Public Benefit Proposal for Mass Tort Villains.

Copyright © 2023 Creditor Rights Coalition. All rights reserved.

1 Over 95% of the personal injury classes voted to accept the plan, though a significant number of claimants did not vote at all.

2 Professor Levitin has argued that bankruptcy courts do not even have the authority to grant consensual third-party releases when claims are not ripe and estate property is not involved. See Adam J. Levitin, The Constitutional Problem of Nondebtor Releases in Bankruptcy, 91 Fordham L. Rev. 429 (2022).

3 See Samir D. Parikh, The New Mass Torts Bargain, 91 Fordham L. Rev. 447 (2022).

4 See id.

5 Consensual third-party releases may be easier to secure outside of the mass torts context in cases with limited numbers of creditors.

Read our recent coverage of Purdue Pharma

click through to read the features from our Contributors

Hip Hip Hooray!

Rite Aid prepares for BK

WeWork on the ropes…

MNK prepares for Chapter 22

Exclusive Content

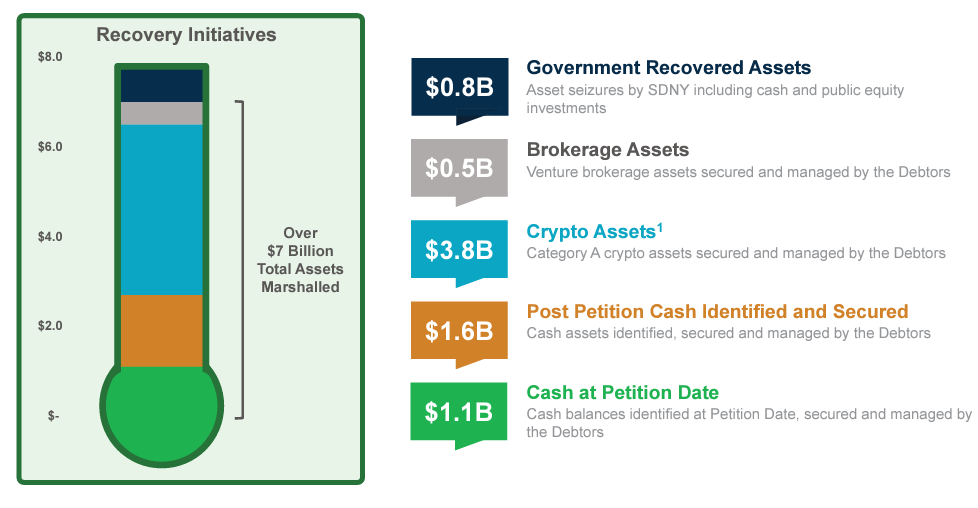

FTX marches on…

Exclusive Content

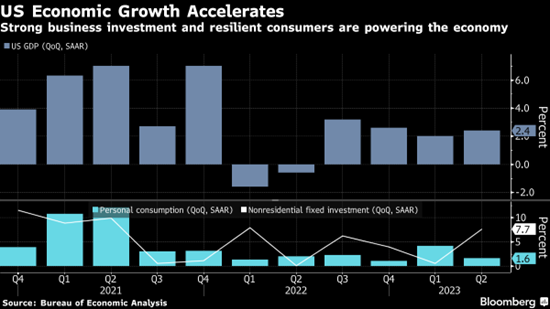

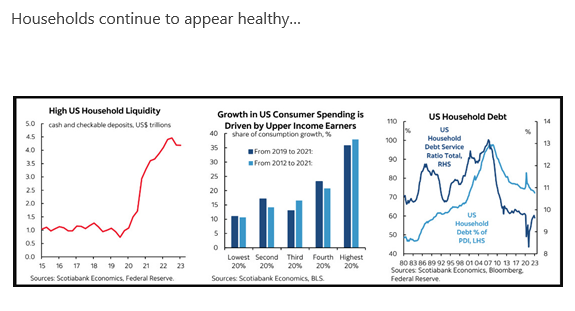

Goldilocks moment?

Or, just the calm before the storm…

As pointed out by our friends @Petition

Check out Petition here

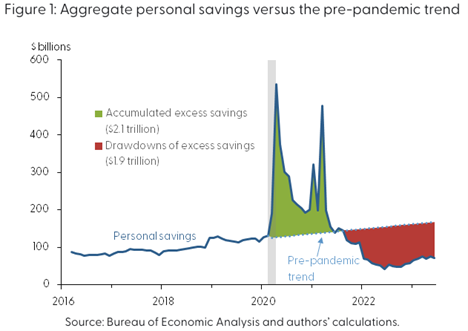

Is the consumer about to break?

2023 CRC Allocators Conference

Beard Investing Conference

CRC weighs in on Serta

Contributors Speak Up

What to expect in the next default cycle

We asked Contributors Bradford Sandler and Sidney Levinson to weigh in on what we should expect in the next default cycle.

Professor Edward Altman recently noted in a paper published with the Creditor Rights Coalition that the Benign Credit Cycle is over. He sees a reversion to the mean in terms of defaults and recoveries in 2023. But he also sees many risks on the horizon making a Stress or even in a “hard-landing†scenario a possibility (with 8-10% default rates). Put your prediction caps on. What do you see and expect? Where do you expect restructuring activity to increase? Are we in for more bankruptcies? Or, more (yawn yawn) extend and pretend? Will RSAs rule the day? Or, will we see more traditional in-court restructurings? What will this new environment look like?

Read our recent coverage:

Where Are We In The Credit Cycle?

Look out for more great features from our Contributors

Have something interesting to share?

email us at info@creditorcoalition.org

Upcoming Events

August 29: Kobre & Kim: Country Garden Cross-Border Opportunities

August 30: ABI Commercial Real Estate Market Outlook

September 29: ABI: Views from the Bench