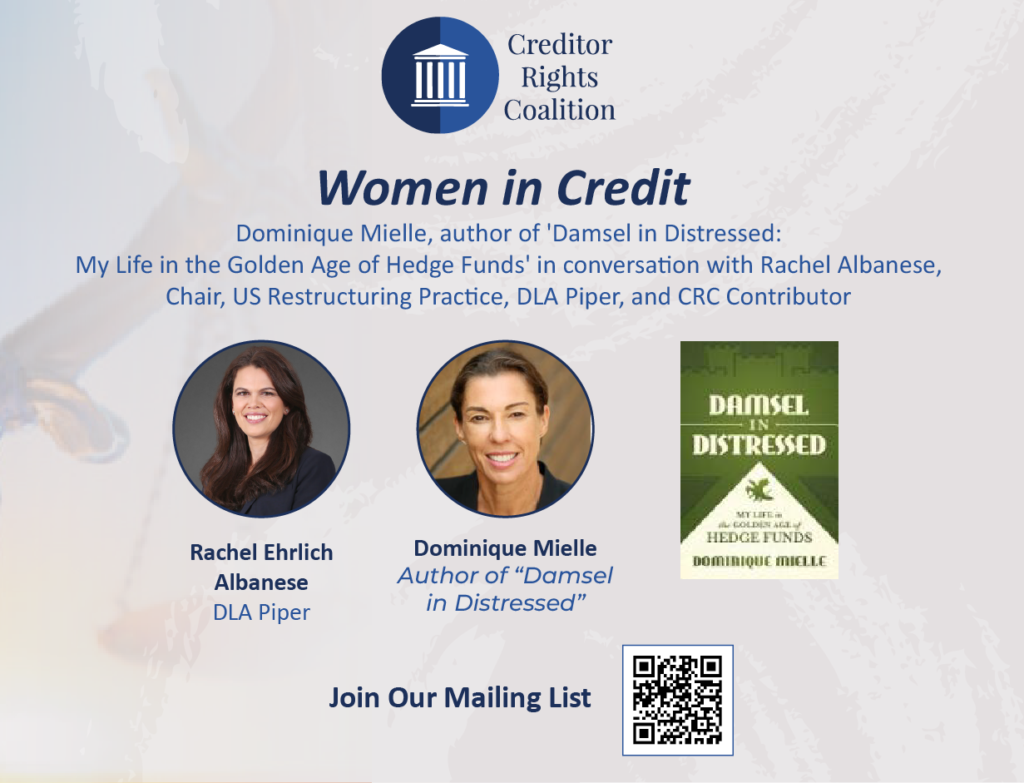

Special Feature: In conversation with Dominique Mielle, author of Damsel in Distressed

CRC Contributor Rachel Ehrlich Albanese speaks with former hedge fund manager Dominique Mielle, author of 2021’s Damsel in Distressed: My Life in the Golden Age of Hedge Funds. Mielle spent two decades as a partner and senior portfolio manager at Canyon Capital Advisors and was named one of the “50 Leading Women in Hedge Funds” by the Hedge Fund Journal and E&Y.

Rachel Ehrlich Albanese:

You are one of the pioneering women in hedge funds. Today we are going to talk about what it’s like to be a woman on Wall Street. You came up with a very clever way of describing the situation that many women find themselves in, in this male-dominated industry. Can you talk about what you described as the “quicksand floor”?

Dominique Mielle:

I was thinking about how I felt when asking for either more capital, or a promotion or a business to lead, or a meeting to head. And it’s not so much that I thought I was hitting a ceiling, it’s that I thought it was hard to take off and that I needed to be more aggressive, more persistent than my male colleagues. I really had to put myself way, way out there to get what I thought was sometimes sort of pretty obvious to get, and in talking to other women in similar situations, I found that they felt the same. Women can get to a point where everybody’s comfortable with where they’re at, and when it comes to taking a step up, there’s this quicksand that drags you down.

Rachel Ehrlich Albanese:

It really resonated with me. I’m sure it will resonate with others.

So now let’s talk about current events.

In your book, you write about the financial crisis in 2008 which clearly had a deep and lasting impact on you as a person and a professional. In fact, you wrote that the mere mention of it gives you heart palpitations. So I apologize if I am causing you some of that now, but the timing of this interview couldn’t be better. In your book, you draw some clever parallels between the Dutch Tulip Mania of 1637 and the Great Recession. Can you talk about some of the parallels between the banking crisis that started just a little while ago and what happened in 2008?

Dominique Mielle:

Well, I think there are many parallels. In a way, I look at the shotgun wedding of UBS and Credit Suisse, and the first thing that comes to my mind is nothing is new on Wall Street, but on the other hand, the causes and the symptoms are very different. What’s similar is that systemic financial risk shows up very quickly in the banking system. And when it has the scale and the size of a Credit Suisse or several regional banks, then it must be addressed. And, I have to say, I thought the speed of the reaction in the US and Switzerland were pretty impressive. Certainly, there’s been great learning lessons from 2008, right?

It took a lot longer than that in 2008. The FDIC acted extremely quickly, and Credit Suisse was done literally over a weekend. Of course, the reasons are so different now. I don’t think there’s a liquidity crisis, which really was the case in 2008.

In a way, you can say that there’s always a mismatch between assets and liabilities of a bank, right? They take deposits that are short term and they put it in assets that are longer term. That’s how they make money. So this mismatch is nothing to be outraged about. In Silicon Valley’s case, the mismatch was extraordinary and made more pronounced by management decisions to go longer on the maturity side of their assets. The fact that their deposits were from very sophisticated businesses that could flee very quickly accelerated the whole melt-down. Credit Suisse was sort of a slow train wreck that came to a final stop over the weekend.

I was thinking about this today. Wall Street repeats itself. It’s very helpful to have people who have tenure and who have seen that story before. They have the mindset that, okay, I’ve seen this, so I know what different moves can happen and then adapt to the scenario that’s unfolding today.

Rachel Ehrlich Albanese:

From my perspective, I was watching very eagerly to see whether they would cover the uninsured deposits because of the nature of the customers that used Silicon Valley Bank. So many emerging growth companies would’ve suffered if they weren’t able to access that cash to make payroll.

Dominique Mielle:

There’s always the other view, and I think Ken Griffin was raging about what he called the bailout of the depositors and that Silicon Valley shouldn’t have been rescued. But I thought this would’ve been hell if they had let it fail and let depositors take a loss. It would’ve triggered a whole other level of disaster. And the idea that there’s a way to deal with this without saving uninsured depositors to me was ludicrous.

Rachel Ehrlich Albanese:

I really liked it in your book where you made the point that 2008 was the equivalent of Murder on the Orient Express, in that everyone was at least partially guilty for the financial blood bath. Do you have a view on who or what is to blame for the current situation?

Dominique Mielle:

My only sense is that there’s not one person to blame and that there’s a confluence of factors that played a part. Is there management error? In hindsight, the extension of maturity was a terrible decision and terrible timing. And I think you could probably also say that the audit committee was asleep at the switch or didn’t really understand what a 300, 400 basis point change in treasury rates would do to their book. So that’s one. There’s also the fact that depositors were concentrated. And, there’s also the fact that Peter Thiel tweeted a day before the weekend to take their money out. That doesn’t help anybody. That creates a wave of panic. So I think there’s just a whole bunch of factors.

Rachel Ehrlich Albanese:

I think social media really does play an outsized role in the public reaction to these kinds of events.

Dominique Miele:

It’s a huge impact, particularly for this industry because a run on the bank is really what did those banks in. This is, in great part, a matter of perception and of how safe a bank is. And, in that context, social media can completely undo a financial institution. That’s a new phenomenon. I wonder what would’ve happened in 2008 if we had that level of communication. It can really become a weapon that’s very destructive.

Rachel Ehrlich Albanese:

What impact do you think greater board diversity would have had on the current crisis?

Dominique Mielle:

I’m not sure, but as a general rule, the research is pretty adamant, specific and convincing that diversity on the board, like diversity on any decision-making body, leads to better outcomes. Diversity doesn’t guarantee success, but lack of diversity certainly guarantees non-success. And we shouldn’t be confusing both. It is not some panacea, it is not a recipe for the optimal outcome in every single instance. But, research shows that on average, a diverse group makes better decisions. And that’s what I believe.

Rachel Ehrlich Albanese:

I totally agree with you. It’s a false dichotomy to say that it’s a diverse board and it failed, so, therefore, diversity doesn’t work.

Dominique Mielle:

That’s so dumb because how many non-diverse boards can you point to that have failed, right? So, that sort of logic does not fly.

Rachel Ehrlich Albanese:

I agree with you.

Now, let’s turn to a recurrent theme. The Creditor Coalition has talked a lot about “creditor on creditor violence.” Some people have begun pushing back on that description. They prefer to reframe the transactions as liability management exercises in which investors are merely taking advantage of loopholes and existing provisions in debt documents. You have commented about “polishing” terminology in the hedge fund context. It seems relevant in this context too.

Dominique Mielle:

Yes, we used to call them “junk” bonds, now they’re called “high yield” bonds. We used to be called vulture investors, now we’re called distressed investors. I think it’s the normal path of every new venture that, as it becomes bigger and more established and more institutionalized, we find more glamorous names or more acceptable names. So it only makes sense that “creditor on creditor violence” is simply liability management.

Rachel Ehrlich Albanese:

Do you have a view on any of those liability management transactions?

Dominique Mielle:

I’ve been the victim of some of them. J Crew back in the day when the IP was transferred out. I have several views. One is that it’s fair game. As you said, it’s a creditor taking advantage of a loophole or a poorly or sloppily written document. You know, if I were on the other side, I would do the same. In fact, I’ve done the same before to defend my position because that’s my duty as a hedge fund investor to protect my interests. We all know that’s sort of what distressed investing is. And in many instances, that’s what makes it so thrilling and exciting is to find that one term that can change a losing trade into a winning trade. So, I think it’s to be expected.

At the same time, when I look back and reflect on how the Bankruptcy Code was written from the Chandler Act to the 1970s reforms, it seems to me that bankruptcy in general, but particularly Chapter 11, was a process of equity with the goal of distributing fairly or equitably the estate to the different stakeholders. And that obviously is lost in today’s process.

But at the same time, I think different stakeholders have power at different times. One of the stated goals of Chapter 11 is saving jobs. I think that power is finally tipping to where labor is going to be a greater force to reckon with in future years. The idea is that it’s hard to find labor. It’s hard to build a workforce. I think we might see legal advisors, boards, management teams, and financial advisors spend a lot more time on how do we pay our labor? How do we keep them, how do we increase retention.

Rachel Ehrlich Albanese:

That’s fascinating. I haven’t really heard that much about a focus on labor as a trend, but it does make sense.

In your book, you had some thoughts on what successful investors do, what types of skills they demonstrate. Can you talk about what you see as skills for success in investing?

Dominique Mielle:

It’s a lot about creativity. It’s a lot about ingenuity, being a good listener. Those skills are generally not what you imagine a hedge fund investor is. And that’s certainly not how they’re portrayed in the media or how they even define themselves. Particularly in restructuring, it’s hard to get people to coalesce around a plan. It takes imagination to think about what is going to work, and then it takes persuasion to get people to rally around your idea.

I always felt it was a tremendous outlet for imagination and creativity. Of course, when I say that to my kids, they usually think, well, you can’t sing, you can’t draw, how are you creative? But if I look back at my career, that is really how I express my creativity.

There’s still the stigma that men are better at risk taking, that they’re better at numbers, that they’re better at math in general. They’re more aggressive. So if you frame success as an investor in those terms, then you’re gonna get a very male-driven image of a role model. If you say creativity, ingenuity, listening, patience, negotiating skills, then I feel like it’s a whole different type of person. It’s a gender- neutral description. And to me, I think it reflects the reality of the job.

Rachel Ehrlich Albanese:

Sometimes successful investors are not always successful. You discuss some really interesting formative failures in your book. Can you talk about one or two?

Dominique Mielle:

It’s a lot more fun to talk about success, but one of the biggest losses early in my career was Worldcom. It was absolutely searing because I was coming into the job and sort of progressing towards having my own book of business, and I was just completely taken aback by the accounting fraud and how quick the demise of the company was. Within an hour, bonds dropped from 90 to 20 or even less. And then I look back and think what did I do wrong? Of course I did some stuff wrong, but it’s also that sometimes the process is right and the outcome is wrong. And that is kind of the lesson of the job, which by the way, is super helpful to live your life by, you can have a good process and shit happens, and then you just have to take it and move forward and reassess. That’s the only thing you can do. And the right way to do it is really to start from scratch. In that instance, I was a very young analyst, and the ability to reassess was very much helped by the founding partners. But it’s very hard to start from zero. Generally, you think of a good investor as somebody who always wins, and nobody tells you that everybody loses a lot all the time. It’s the law of averages. But you don’t know that when you start, you think that the first loss is going to end your career. And certainly, I just wanted to crawl into a hole and be left alone for the remainder of my life. So it’s a good thing that I’ve learned how to climb out of that hole.

What’s interesting is that, at least for me, there was a lot of shame. It’s not only that you feel bad about losing money, you are incredibly ashamed of the decisions you’ve made. And it’s quite isolating. We’re talking 20 plus years ago, and it’s not like I had a network of young hedge fund friends who said, “Hey, don’t worry about it. I lost a ton of money too.†So how would you know that it’s happened? And by the way, not only to young investors, but to everybody at the highest levels, at the legend level of Ackman and Tepper, they lose a ton of money too, but, but it’s not something that you’re aware of, right? It’s certainly not something that you read about, at least not 20 years ago.

Rachel Ehrlich Albanese:

You wrote that you believe social mobility is still possible on Wall Street, and I noticed that your examples might arguably be from a bygone era. How does someone without the right education or connections get a job on Wall Street?

Dominique Mielle:

Part of the reason I wrote the book is I was thinking about how people were protesting how much money bankers and investors make. And it’s true. It’s astounding. And I was thinking, well, wait a minute. That is true, but it’s still one of the few jobs, maybe along with sports and Hollywood, where you really can start from zero with no network, no connections and with sheer skills and brute force, you can really become a multimillionaire, if not a billionaire. So there’s something that is actually perversely fair about this job, right?

I didn’t have connections. I didn’t have a network. And yet I had a tremendous career. Now, if I look with a wider lens, I can see how yes, I had a great education. I went to Stanford. My parents were educated people. We are sort of upper middle class in France. I can see that I had enormous privileges. So, is there social mobility in finance? Yes, there is, but the problem now is how can you get into the right colleges, the right business schools. If you are a minority, if you are not upper middle class, it’s hard. It’s very hard. So I think in finance, like in almost all aspects of society, we are very much stuck in a system that promotes the same sort of people.

Rachel Ehrlich Albanese:

Now let’s talk about one of your great successes. You came up with the concept of a capitalized manager vehicle (CMV) to ensure that Canyon CLOs complied with the original Dodd-Frank restrictions. Can you tell me about how that works and why it was so successful?

Dominique Mielle:

I was not alone. We worked as a team, with the help of a people at Canyon, at Goldman, and a team of lawyers. This was a structure that was meant to address the Dodd-Frank reforms that required issuers of CLOs to own a tranche of the equity. What we did is create a fund similar to a private equity fund where the issuer, meaning Canyon, put in some money, and we raised the rest. And that pool of money was available to issue CLOs that conform to the Dodd-Frank retention rules.

CLOs are an incredibly resilient and attractive investment vehicle. And this is really, an example of being creative at a time when the retention rule was viewed as a real disaster for the industry. The first thought of all participants was to fight it. Then, in talking to the partners at Canyon, we thought, well, wait a minute. What if, instead of fighting it, we found a way to be the first to satisfactorily address it. That was a great joy in my career, to turn a problem into a marketing and an investing advantage. That was great fun.

Rachel Ehrlich Albanese:

That’s a big accomplishment.

Are there any other investments or experiences that you’re particularly proud of over the course of your career?

Dominique Mielle:

One of the most challenging but also interesting experiences I have had is serving on the board of directors of Pacific Gas & Electric during its bankruptcy. One of the challenges was that it was not only a restructuring, but it was also a human disaster. There were many lives lost and homes destroyed, but the challenge was to get PG&E back on its feet and out of bankruptcy within 18 months. And that was incredibly difficult. We got it done with a great bunch of people on the board. It was a tremendous adventure.

Rachel Ehrlich Albanese:

So let’s talk about the reasons why people used to invest in hedge funds and the reasons why they’re investing today.

Dominique Mielle:

The origin of the hedge fund industry was to provide the ability to truly hedge the market, meaning have positive returns in good and bad times. And this was true for many, many years, right? I would say at least from the late nineties to 2008, there was a consistent outperformance by hedge funds in general. But that changed in the years subsequent to the financial crisis. Since then, the hedge fund business as a whole has outperformed the market in maybe one in nine, 10 or two in 15.

That doesn’t mean that some hedge funds don’t beat the market sometimes, of course they do. But it does mean that on a persistent basis, the industry taken as a whole does not fulfill that promise anymore. So the question is, why should you invest in hedge funds today? There are many reasons. For example, for diversification or because you might pick the right hedge fund at the right time and outperform that year. Those are valid reasons. But the issue is if you’re buying diversification or timing, how much should you pay? And that’s very difficult to answer.

Rachel Ehrlich Albanese:

I thought you raised some interesting questions about whether we are doing this because we’ve always done this, or is this something that’s actually generating better returns and value?

Dominique Mielle:

Correct. And it’s worth thinking about it because the hedge fund business is a very mature industry at this point. This is not 20 years ago where you had the wild cowboys in a scrappy industry. By and large, the market is institutionalized, with tremendous scale. So it matters to know what exactly you are offering as a product and how you should price it and how you should market it.

Rachel Ehrlich Albanese:

What advice do you have for young professionals, meaning analysts, bankers, law firm associates?

Dominique Mielle:

I always get stumped by that question because how am I going to give relevant advice to an American woman from a small town versus an international student? One thing I’d say is a lot of what makes a career is sticking with it, and to stick with it, you have to love it. It’s not a matter of wanting to make money or wanting to brag about an industry. You really should love it.

And that doesn’t mean you have to love trading. It might, but it might also mean you love detective work. I can see how I’m a problem solver and I would have the patience to go through a thousand page 10-K to really understand the balance sheet, the waterfall of a securitization. I’m a studious, tenacious person, and I really want to be out there making decisions. If you have any of these qualities, or if you really love the idea of being an investor or a lawyer or an investment banker, that’s it for you. All other sort of reasons are going to make it really tough to stick with it.

I think restructuring is fantastically interesting. It really is a game of risk where you move your pawns and it’s just a thrill. It’s great fun. Great, great fun.

Rachel Ehrlich Albanese:

I agree. And I think that’s the perfect note to end this on. Thank you so very much.